Help sometimes comes from the most unexpected places. One may be forgiven for thinking that an imprisoned Japanese foreign officer who himself didn’t even like living in Singapore, would probably not help locals in their hour of need. And yet, help he did, saving thousands of lives in the process.

Being in Singapore was never a desire of Mr. Shinozaki. He much preferred the post of press attaché in Germany, where he had originally been posted by the Information Bureau of the foreign office in Tokyo. In some ways, the posting to the island, with its durian smells and heat, felt like punishment for his behavior in Germany. After all, he had had an affair with a German woman and gone travelling around Europe without the permission of the Japanese Ambassador to Germany. Unfortunately for Mr. Shinozaki, it would seem that the punishment continued even after his arrival in Singapore. While working as a press attaché for local Japanese newspapers, he was arrested for spying and sentenced to three and a half years in prison. He had apparently, on orders from Japan, befriended British officers to find the whereabouts of heavy guns.

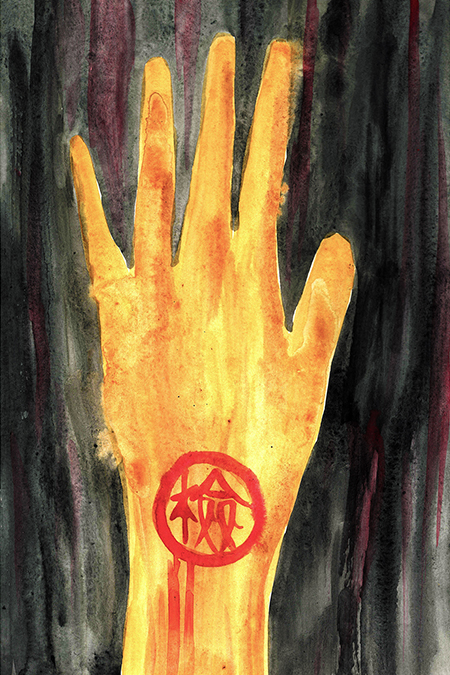

This punishment was however cut short. On 12 February 1942, the cries of some prisoners rung out “The Japanese are coming!”. And come they did, on the 15th of February, the Japanese stormed a deserted prison, to find Mr. Shinozaki in the tower. He was taken to the military headquarters and assigned the post of Advisor to the Defence. His role was to protect neutral parties, Germans and other Japanese people living in the city. For this task, he was given protection cards which he would give out to “good citizens”. Unbeknownst to the Japanese, Mr. Shinozaki would expand this definition of “good citizens” and save thousands of lives.

Mr. Shinozaki had decided that it was not only neutral persons and Japanese allies who should be saved. Approximately 30,000 protection cards were given out. As Mr. Shinozaki recounted, “the most important thing was to make it easy for people. Everybody was so afraid; they could not move. So the first thing was to give them freedom to move about.”

Around this time the Japanese began their plan to round up the Chinese men, for what would be later known as the Chinese massacre. Mr. Shinozaki would do more now than just hand out cards. He would visit concentration camps and detention centers, using his rank to set Chinese men free. Chinese women from across Singapore would visit him and implore him to help their fathers, brothers, and relatives, and he would turn no one away. At the time, there were five main concentration camps. At some camps, like the one in Jalan Besar, it was relatively easy to get people out, but in others like Tanjong Pagar and River Valley, it was near impossible.

For the more difficult camps, Mr. Shinozaki would employ a different method. He would assist in the creation of the Overseas Chinese Association. On the surface the association’s aim was to facilitate cooperation with the Japanese army, but as Mr Shinozaki would later recount, its true function served a more noble cause.

To release the Chinese men from Tanjong Pagar, many of whom were influential Chinese leaders, Mr. Shinozaki needed a good reason. He would explain to his Japanese superior that influential Chinese leaders were needed to foster cooperation in the association. Hence instead of sending these men to die, they should be released to help in the association. In his memoirs Mr Shinozaki recounted how the men previously unreachable in Tanjong Pagar and River Valley were subsequently released.

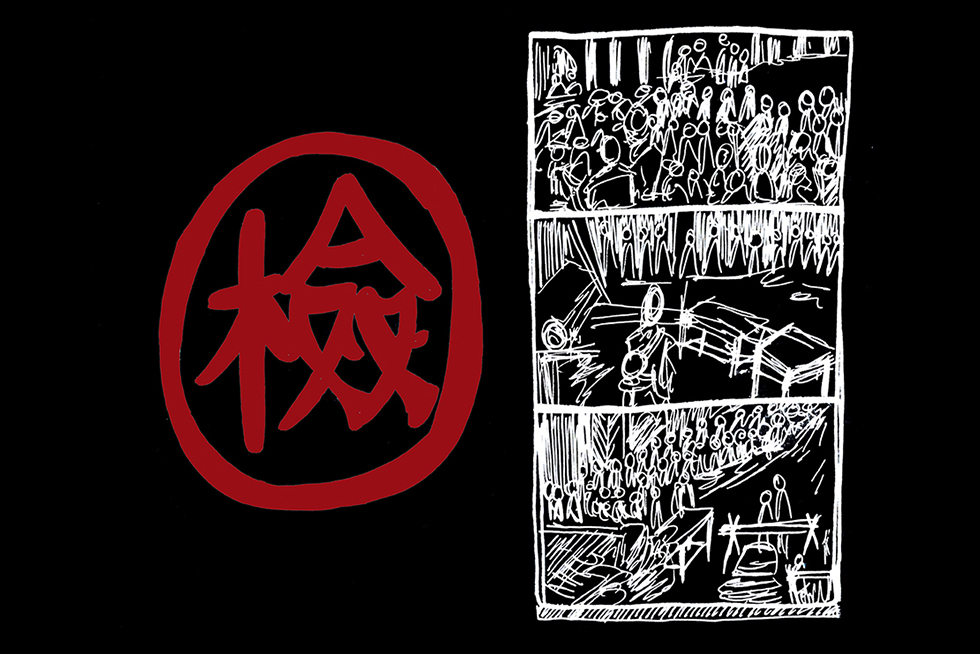

Even after the war ended and the Japanese retreated, Mr Shinozaki would perform yet another service. During the war crimes trial in Singapore, he would serve as prosecution witness testifying against the Japanese officers for their crimes.

It is unclear the total quantity of lives saved as a result of Mr. Shinozaki’s efforts, but it is arguable that without his intervention, the death toll of locals would be much higher.