LAWS

The 1945 Royal Warrant authorised the British military to establish military courts to try and punish “violations of the laws and usages of war” committed in any war that the British had been engaged in after 2 September 1939. The Royal Warrant came with a set of regulations.

In Asia, the 1945 Royal Warrant was supplemented by ALFSEA Instruction No. 1.This army instruction set out a list of acts or conduct that would qualify as war crimes, but the rest of the instruction largely dealt with procedural and administrative matters rather than substantive law. Nevertheless, as the Warrant required these courts to be considered “Field General Courts-Martial”, trial personnel cited a mixture of international law, British military law, and English criminal law in these trials.

LEGAL ACTORS

Each court established under the 1945 Royal Warrant comprised at least three judges. Prosecutors were generally from the British military. Accused were to be represented by counsel and were so represented in all trials, though counsel usually represented several accused in joint trials. If defendants were represented by Japanese defence council, a defence advisory officer from the British military would usually be assigned to the defence team to assist on matters of procedure.

From 1946 to 1948, the British tried over 400 accused linked to the Japanese military in Singapore for war crimes committed not only in Singapore but throughout Asia. The majority of these accused were from Japan. A small minority were from Korea and Formosa or present-day Taiwan.

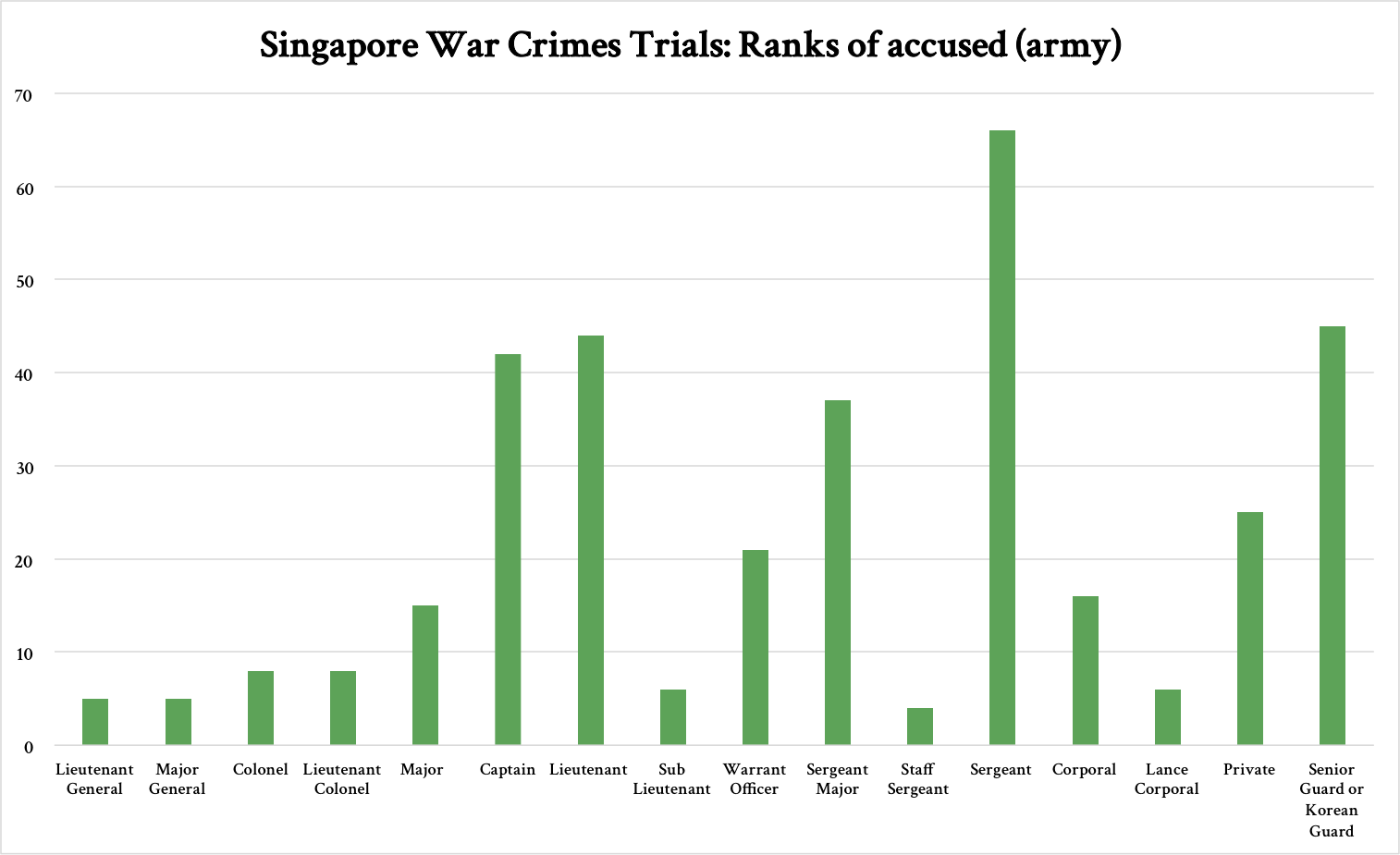

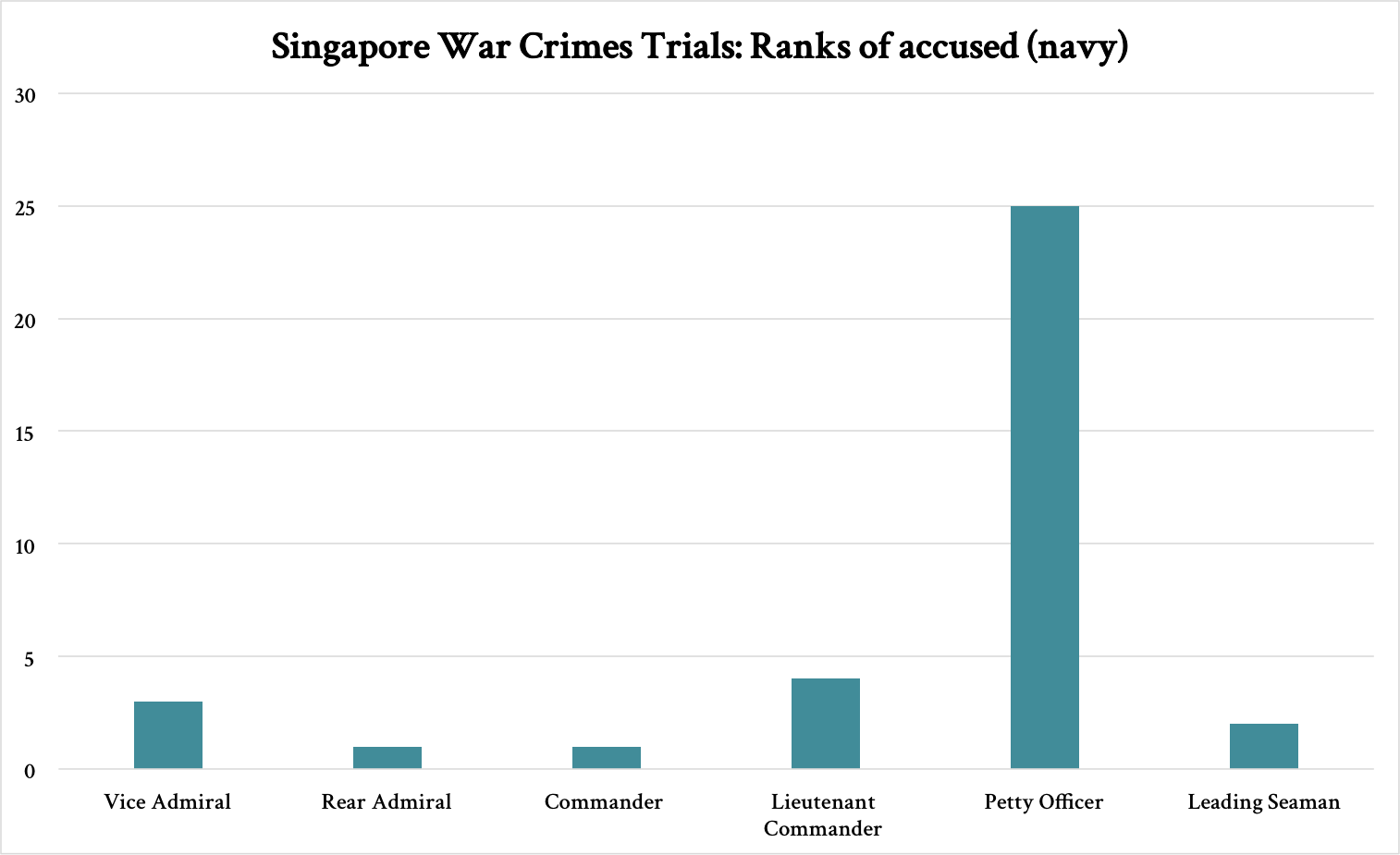

The over 400 individuals prosecuted for war crimes in Singapore held a variety of positions and ranks. The highest rank held by an accused from the Japanese army was that of lieutenant general, the second highest rank assigned by the wartime Japanese military. The lowest rank held by an accused from the Japanese army was that of private and guard. The majority of those prosecuted in the Singapore Trials held low to mid-level positions of responsibility. Based on their ranks, sergeants formed the largest group of accused from the Japanese army. Petty officers formed the largest group of accused from the Japanese navy.

These British military courts were authorised to pass sentences of death, imprisonment, confiscation, and fines. Sentences of death could only be passed with the agreement of all judges when the court was composed of not more than three judges. When the court comprised more than three members, at least two-thirds of judges including the president needed to agree on the death sentence.

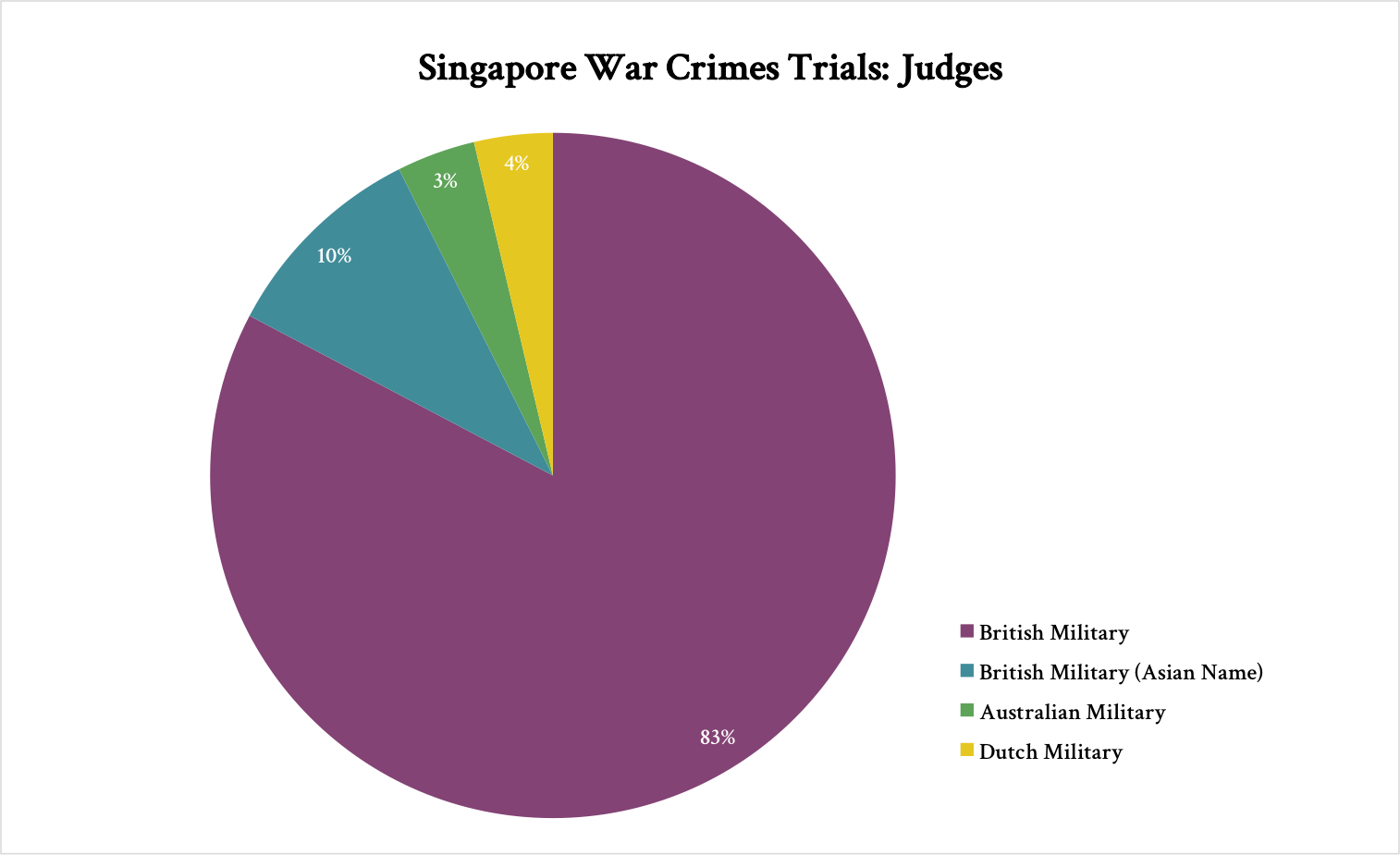

A number of judges in the Singapore Trials had Asian names and were from the British Indian Army. However, it should be noted that not all judges from the British Indian Army were of Asian ethnicity.

The warrant authorised the British military to invite military personnel from other Allied militaries to serve as judges. A number of trials featured judges from other Allied militaries.

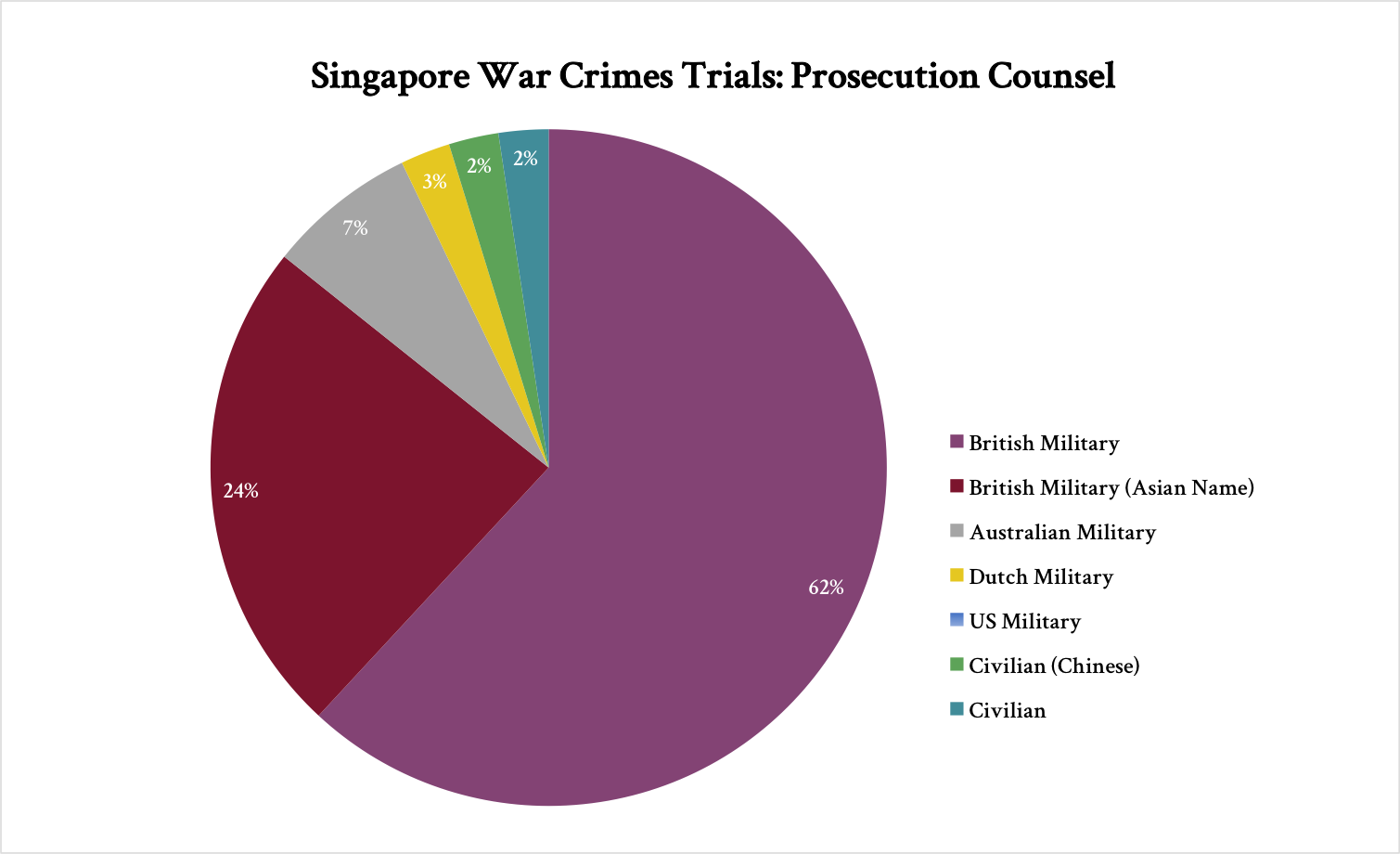

The majority of prosecutors in the Singapore Trials were from the British military. In some cases, personnel from other Allied militaries served as prosecutors in cases with victims of the same nationality as that Allied military.

There were only two civilians who served on prosecution teams in the Singapore Trials.

John Eber, who acted as counsel for the prosecution in several trials, was from a prominent Singapore Eurasian family and later became an important player in Singapore’s left-wing politics. Eber had himself been detained during the war. Richard Lim Chuan Ho was the only Chinese civilian who served on the prosecution in the Singapore Trials. Lim was on the prosecution's team for the first Sook Ching Trial (Nishimura Takuma and others). Lim later served as Deputy Speaker in Singapore’s Legislative Assembly during the country’s transition to independence and founded the Singapore Overseas Union Bank.

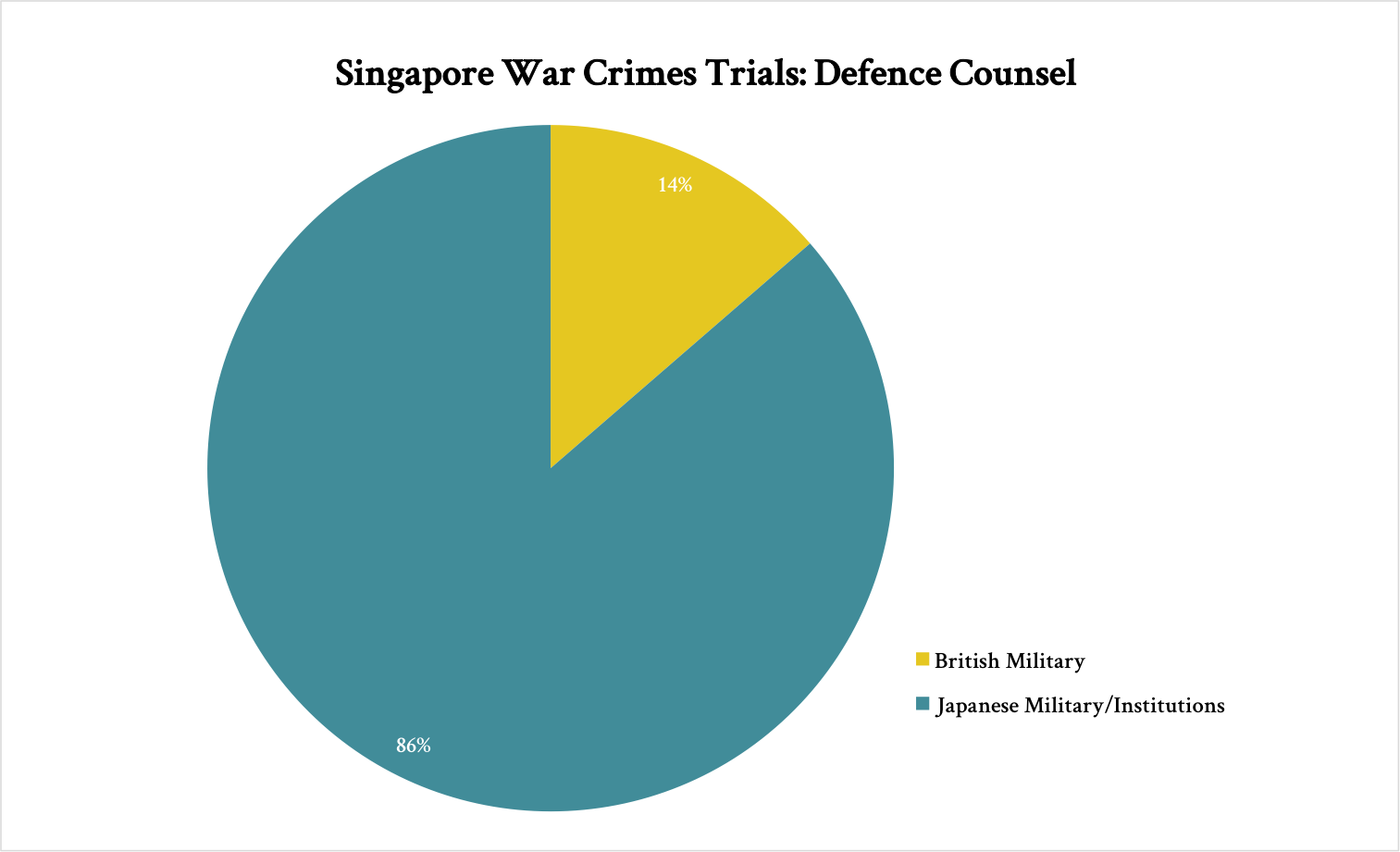

In the first few Singapore Trials, accused were defended by British military personnel. However, due to a serious shortage of legally trained British military personnel, most accused in the Singapore Trials were defended by Japanese defence counsel. In such cases, a defence advisory officer from the British military was usually assigned to the defence team to advise on procedure.

LEGAL PROCESS

The British military's courts established to try war crimes under the 1945 Royal Warrant were military courts.The 1945 Royal Warrant required these courts to be treated as “Field General Courts-Martial” unless expressly or by implication required otherwise. Field General Courts-Martial were more lightly regulated than other courts-martial in the British courts-martial system. The 1945 Royal Warrant simplified trial procedure even further by expressly exempting its military courts from certain legal requirements that would normally apply to Field General Courts-Martial.

In terms of trial procedure, the 1945 Royal Warrant military courts employed a common law adversarial process. The 1945 Royal Warrant and ALFSEA War Crimes Instruction No 1 also authorised these courts to take a less formal approach to evidence and ensure expeditious proceedings.

British leaders intended these trials to be expedited in nature. These courts were to conduct as many trials as possible over a short period of time. ALFSEA Instruction No 1 emphasised the “summary nature of trials” and that “justice be administered promptly and efficiently” by these courts. In Singapore, the shortest trial lasted one day while the longest trial lasted 31 days. A trial lasted an average of 6 days.

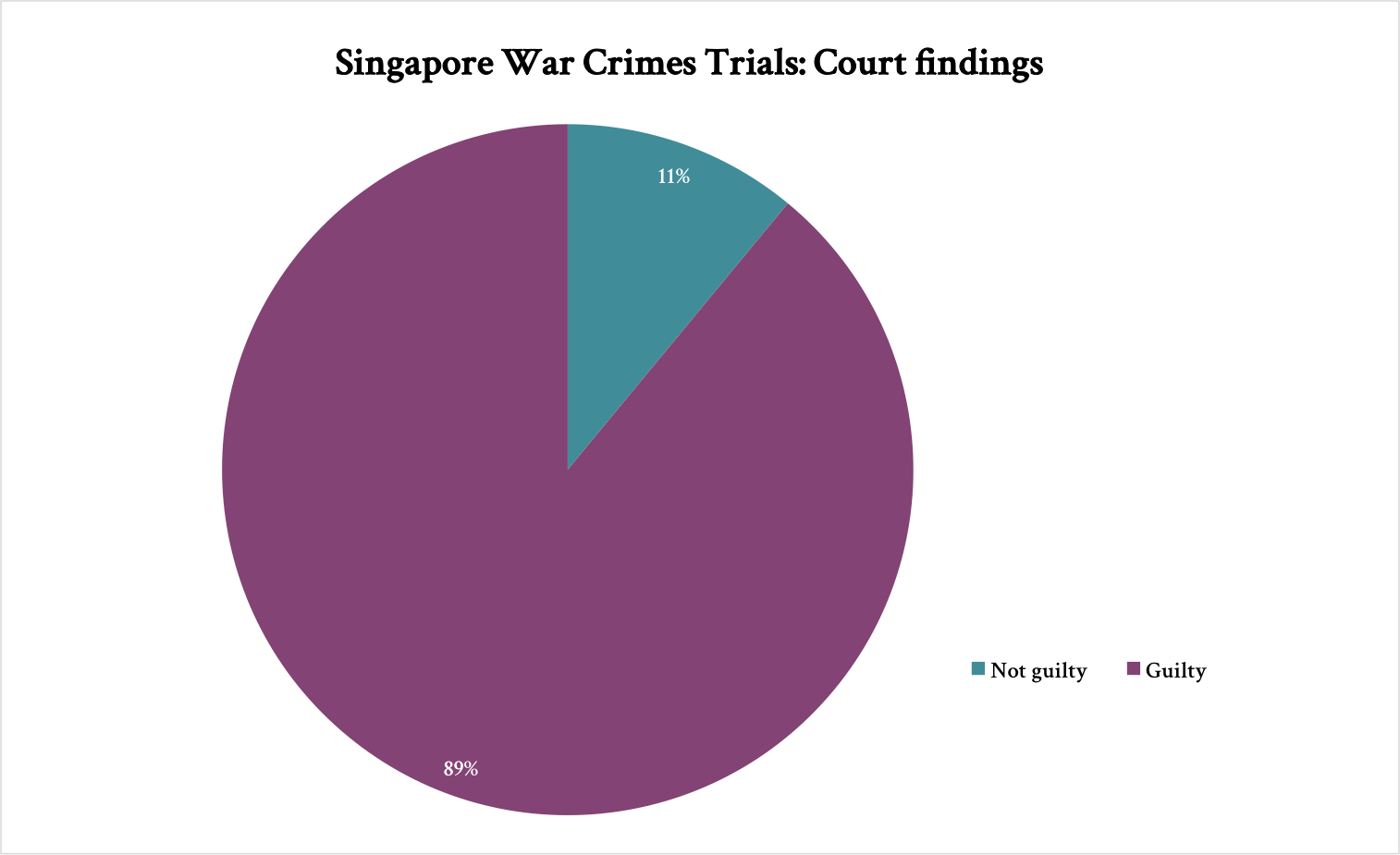

Trial findings and confirmation decisions in the Singapore Trials show that trial actors did try to determine guilt and sentences at the individual level, distinguishing between guilty and innocent persons. 51 accused were acquitted at the trial stage in the Singapore Trials.

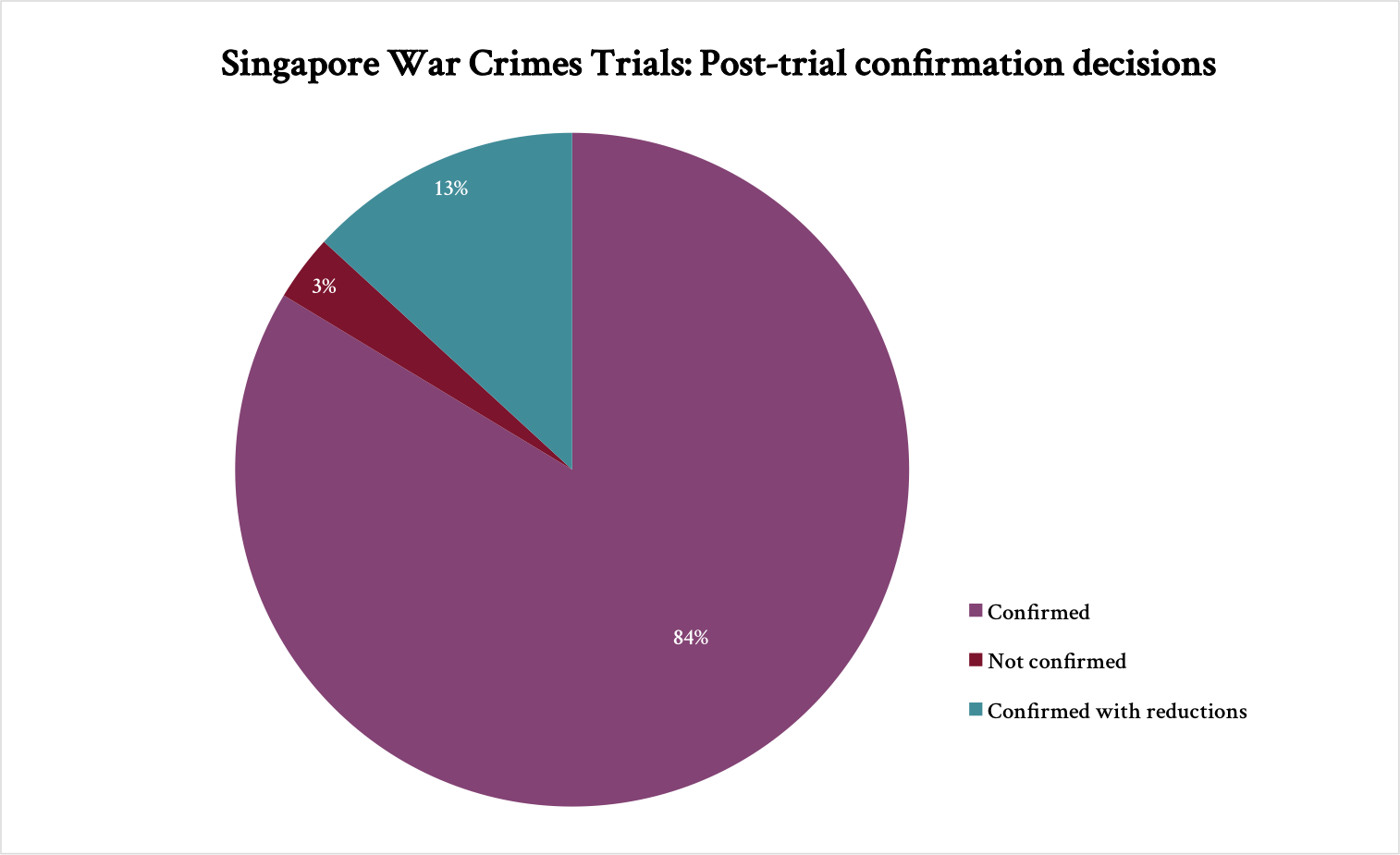

13 trial decisions were not confirmed and 54 trial sentences were reduced at the post-trial confirmation stage.