Richard Lim Chuan Hoe (林泉和)

Born in Singapore in 1904, Mr Richard Lim Chuan Hoe attended St. Andrew’s School. In 1920, he taught at his alma mater, before going on to serve at Anglo-Chinese School till 1924, when he received the prestigious Straits Settlements Government Scholarship to pursue higher education in the University of Hong Kong. Although he initially qualified as a teacher from the University of Hong Kong, he went on to read law in London and was later called to the Bar at Middle Temple. Lim practised law in Hong Kong between 1931 and 1936, before returning to Singapore to join Mallal & Namazie. In 1942, he started his own law firm, R.C.H Lim & Co.

The Japanese Occupation was a very trying period for Lim. Prior to the war, Lim was appointed by the British to be a member of the Municipality, while concurrently holding the appointment as legal advisor to the Chinese Consul-General. His esteemed position in the British and Chinese community led the Japanese to search for him during the war. In the hunt for Lim, the Japanese executed everyone in the Chinese Consulate. Despite his precarious position, Lim’s sense of noblesse oblige motivated him to help the less fortunate who visited him in the middle of the night to ask for money and medicine.

After the war, Mr Richard Lim Chuan Hoe and Major Fredrick Ward served as the prosecuting officers in the Chinese Massacre Trial. The trial opened on 10 March 1947 in the Victoria Memorial Hall, attracting a crowd of 1,200 mostly Chinese civilians anxious to see justice served.

During the trial, the Prosecution asserted that the defendants had failed to protect the basic interests of civilian non-combatants. By carrying out General Yamashita’s order to execute Chinese inhabitants on the island, these men had violated the 1907 Hague Convention that Japan had signed and ratified. The argument that Japan had failed to adhere to international conventions of war became a significant Prosecution thrust during the trial.

At the end of the trial, the Singapore Garrison Commander, Lieutenant-General Kawamura Saburo, and the Commander of the Number 2 Field Kempeitai, Lieutenant-Colonel Oishi Masayuki, were both given the death penalty. The Commander of the Imperial Guards Division, Lieutenant-Colonel Takuma Nishimura, was given a life sentence, while junior Kempeitai officers Lieutenant-Colonel Yokota Yoshitaka, Major Onishi Satoru, Major Jyo Tomotatsu and Captain Hisamatsu Haruji, were all sentenced to prison.

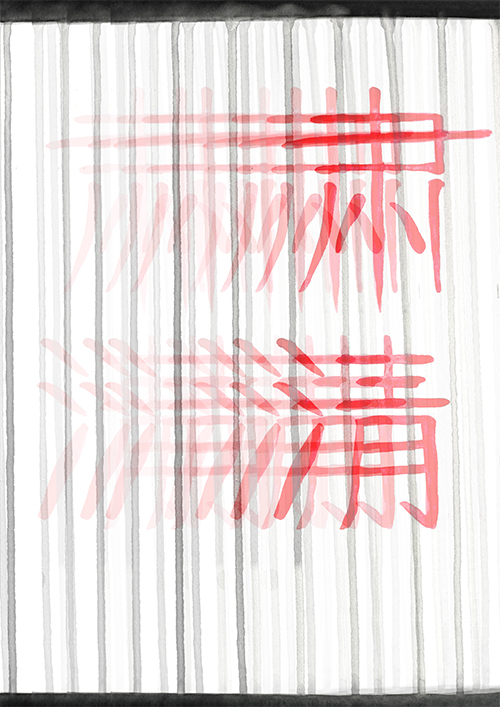

However, Yamashita, who issued the directive to carry out the sook ching (肃清 or purge through cleansing) massacre managed to evade legal indictment for this case. Instead, he was hanged in Manila on 23 February 1946, after being wrongfully accused of ordering his troops to commit atrocities against 32,000 Filipino civilians and American prisoners-of-war.

After the Singapore Massacre Trial concluded, the Chinese Government sent a letter of commendation through the Chinese Consulate in Singapore to Lim, in recognition of his efforts.

Lim remained politically active even after the trial. He became one of the founding Directors of the Overseas Union Bank from 1949 to 1968; and Deputy Speaker of the Singapore Legislative Assembly between 1955 and 1959, where he once candidly advised David Marshall in a letter to learn to accept “serious criticism in the spirit it was offered”. Lim even inspired a young Lee Kuan Yew to eventually become a lawyer.

In 1968, Lim fell ill while on a holiday to Hong Kong with his wife. He was admitted to the University Medical Unit at Queen Mary Hospital, before being flown back to Singapore where he was operated in Tan Tock Seng Hospital for an abdominal aortic aneurysm (enlargement of the main artery). Despite the efforts of surgeons at the cardiothoracic unit, Lim passed away. He left behind his wife Dora Wong Kit King, his daughter Doris Lim Siew Ying and 4 sons – Alan Lim Siew Chuan, William Lim Siew Wai, Arthur Lim Siew Ming and Ernest Lim Siew Yin and 8 grandchildren.