Arthur Newnham Worley’s life was one deeply and tragically affected by both World Wars. His personal experiences instilled in him a fervent belief in the rule of law and a fierce determination to prevent similar atrocities from recurring. It is therefore apt that over the course of his life he served as a justice in the Singapore Supreme Court and in top judicial positions in other jurisdictions.

Born in Surrey, England in 1892 to humble surroundings, Arthur Worley was the youngest of seven children. His father was an upholsterer and an accountant while his mother was a housewife. Despite the difficulties of his time, Worley graduated from the University of London in 1911. Unfortunately, World War One started shortly after and Worley found himself posted to Malaya as a cadet in 1914. While Worley survived World War One, his immediate family did not escape unscathed. Tragically, his eldest brother Bertram met his end in Belgium in 1917, while another brother Robin passed away in Malta in 1915. Despite these personal tragedies, Worley persevered in Malaya and chose to stay after World War One ended.

Worley’s career did not start off in law. After the war, Worley served multiple roles in the civil service in Malaya such as the Assistant Protector of Chinese in Selangor and Perak, and Assistant Director of Education. In 1919, he married Marie de Rochfort Forlong to whom he remained married to for the rest of her life. Worley’s legal career only began at the age of 38 in 1930, when he stepped down from the role of Assistant Director of Education to take on the role of magistrate in Ipoh.

Worley’s legal career blossomed when he left Ipoh and came to Singapore. In 1934, he was appointed deputy public prosecutor in Singapore, and briefly served as acting attorney general of Singapore in 1936. It did not take him long to rise up in the ranks, and he was appointed Solicitor General of Singapore in 1938. This was followed shortly by an appointment as Puisne Judge of the Singapore Supreme Court in 1941.

Unfortunately, the tragedy of war was to strike Worley’s life for a second time. In 1942, Japan invaded Singapore during World War Two and Worley was interned as a prisoner of war. He was interned for the entire duration of the Japanese Occupation of Singapore, first at Katong Convent, then at Changi Prison, and finally at Sime Road Camp. While an internee, he served as the representative for the men in the camp and spoke to the Japanese on behalf of the rest of the interns. Living conditions in the camp were poor, and overcrowding, malnutrition, poor medical care and regular beatings were only some of the difficulties Worley, as well as the other interns, faced in their camps. Serious injuries and death frequently occurred. In 1945, while Worley was still interned in Sime Road Camp, his daughter Phyllis Worley married her husband Major Lynton White in Victoria, Australia. Thankfully, the war ended shortly after and Worley resumed his judicial duties when the British regained control of Singapore.

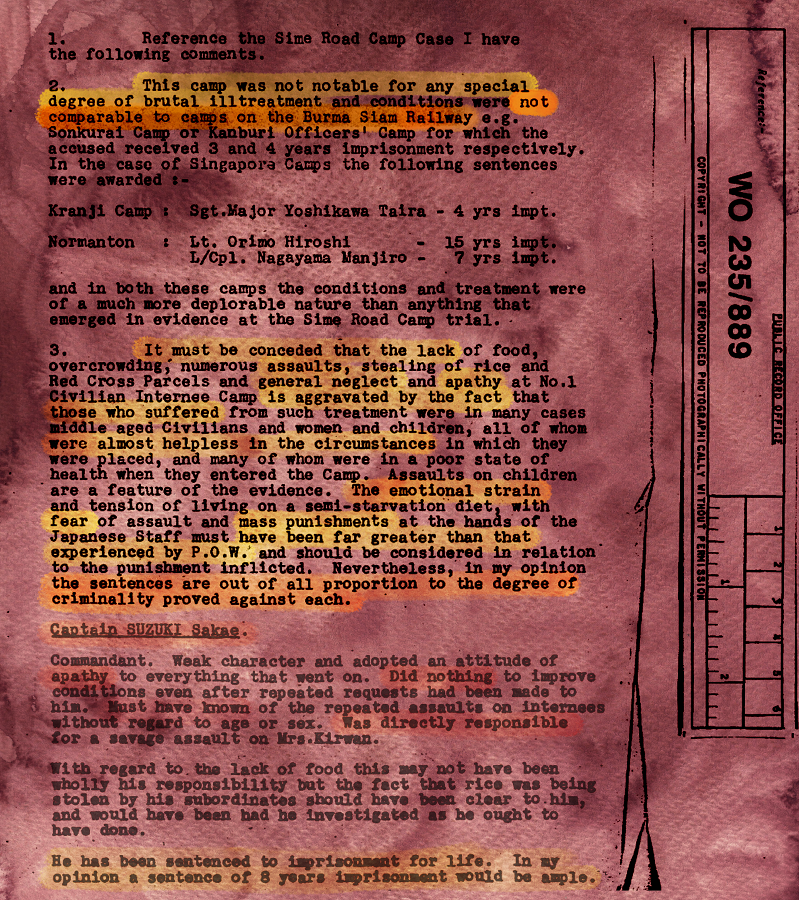

Because of his experiences in the camp, Worley took part in an important trial after the war – but as a prosecution witness instead of a judge. This was the trial of Captain Susuki Sakae and four Japanese soldiers under his charge. These defendants were in charge of the prisoners interned in Worley’s camp during the Japanese Occupation and were charged for causing serious injury to a Gwen Kirwan, and death to a Harold Parker. Both victims were internees in Worley’s camp. The defendants were given sentences ranging from 7 years’ imprisonment to the death sentence. However, their sentences were eventually commuted or mitigated.

Worley’s experiences in both World Wars profoundly shaped his view on the rule of law. He maintained a firm belief that ‘absolute power corrupts absolutely’. He wondered how his Japanese captors while on duty could treat their prisoners with extreme cruelty, yet appear to rediscover their sense of humanity and treat their prisoners kindly once they were no longer tasked with their assignments. This shaped his view that actions and duties justified by the ‘supposed interests of “security”’ can all too easily rob people from recognising basic human rights and dignity. The sheer helplessness and injustice he felt when he was detained under his Japanese captors reaffirmed his belief in a rule of law and a right to a fair trial for all. While he praised the people of his time for passing this test of moral fibre with ‘remarkable steadiness’, he exhorted future generations to ensure that such a disaster must never happen again.

Worley served as a justice in the Singapore Supreme Court until 1946, when he was appointed Chief Justice of British Guiana. He was knighted as a knight bachelor in 1950, and went on to serve as the Vice-President and President of the Court of Appeal for Eastern Africa in 1951 and 1955 respectively. His final judicial position was as the Chief Justice of Bermuda, which he held from 1958 to 1960. He was remembered fondly by his peers as a courteous member of the bar who frequently gave assistance to junior members of the bar.

Marie Worley passed away in 1966. Arthur Worley passed away in 1976.